Nothing loosens your relationship with the material world like clearing your parents’ flat after their demise. You have now become the queen of mortality, the next one to go in the honourable line of existence. All of a sudden, most of the possessions that your parents carefully selected, filed and valued - their pension paperwork, picture frames candle holders, medical prescriptions, clothes, pots, wooden ornaments, artwork which you never quite appreciated - have become redundant. Just like that…in the blink of an eye all these items have lost their meaning and place in the world. They have become clutter, a burden on the planet, a recycling headache.

You are struggling with feelings of guilt that crowd out your grief and sorrow. Shouldn’t you feel more attached to these items that connect you to your parents? To these symbols of their existence, the proof that they were here on earth not so long ago, living and breathing just like you, buying stuff, just like you, resting their gaze on artefacts they had enthusiastically collected over decades, just like you?

Then a wave of awkward laughter comes over you, as you realise that this cycle will go on and in time your possessions will loosen your children’s relationship with the material world; that your children too will struggle to figure out what to do with your material footprint once you have gone. It’s absurdly funny…thinking how much time and effort you have invested in organising stuff that will eventually become clutter. It’s absurdly funny and at the same time terribly sad. You are not sure whether the sadness relates to the eventual loss of meaning or to the inflated meaning that you have loaded onto these material possessions in the first place. Perhaps it is this duality that provokes this nervous chuckle that emerges unbidden, as well as the cry that you gently repress, like the breath you hold in when swimming under water: it has to come out eventually, you just hope it won’t be while you are under.

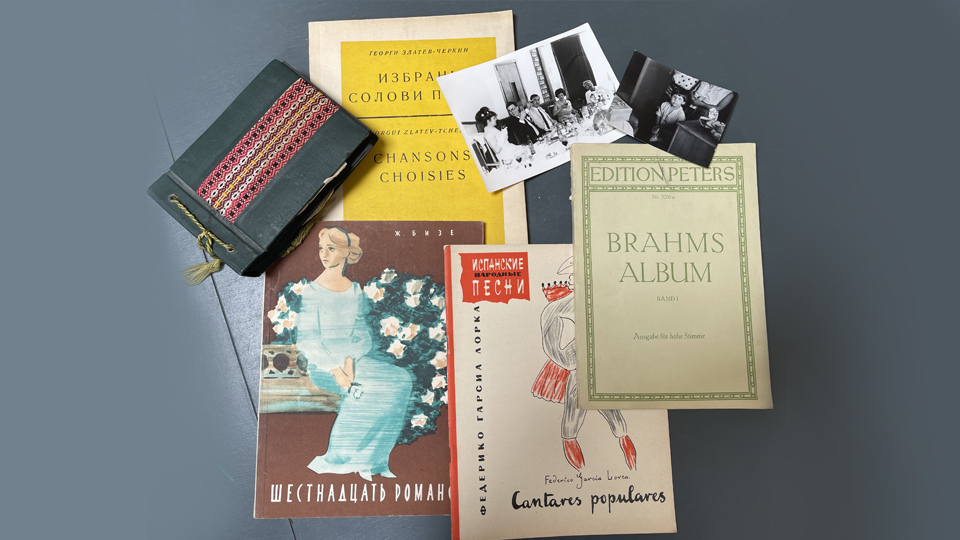

As you plough through reams of things and organise them into four piles - those you will keep, those you will give away to charity, those you will sell to an antiques shop, and those you will throw away - you notice that you’re breathing more easily. You feel that you are operating in a bigger space where there is higher saturation of oxygen. Your lungs feel freer to inhale more deeply and exhale more slowly. Your thoughts keep landing on the precious content of that letter you just rediscovered after having lost all hope; on the photos you saw of your family, taken when you were a girl; on the performance notes that your mum kept from her singing career; on the books in four languages that remind you of the erudite couple that your parents once were. You feel honoured to have been part of this family, you feel grateful that you have these artefacts still in your possession as a reminder of your heritage and your bond with them. You feel pensive. You feel connected. You keep going.