As I am driven in the back of yet another seatbeltless taxi in Sofia, I ponder risk, uncertainty, the impermanence of existence and the latest emerging line of polarisation: whether AI could overwhelm and destroy humanity or whether hypothesising to that effect is simply scaremongering; whether any further development of AI should be regulated as soon as possible or whether it should be allowed to continue developing organically in the race for competitive market dominance, too immature to be regulated.

“We are in defence of the human being”, warns Georgi Gospodinov, author of Time Shelter and winner of the 2023 International Booker Prize, in a recent FT Weekend article. Back in 2019 he argued that if politicians and economists read more literature, the world would be less beset by existential crises. Presumably reading fiction would help them better understand and empathise with people and therefore make better decisions for humanity as a whole. I wonder if this argument should be extended to the handful of AI experts in the world who are shaping our future existence.

Since March this year, Yuval Noah Harari, alongside thousands of other technologists and researchers, has been on a quest to convince decision-makers that any further AI developments should be paused until the use of AI is regulated.

In a recent debate with Meta’s head of research Yann LeCun, he made a clear distinction between intelligence and consciousness, arguing that

“…intelligence is not the same as consciousness. In humans, they are mixed together. Consciousness is the ability to feel things, pain, pleasure, love, hate. We, humans, sometimes use consciousness to solve problems, but it's not an essential ingredient.” We could end up with a god-like smart machine that doesn’t feel. What would happen then?

Last week, some 350 world experts on AI warned us against a variety of grave

dangers it could unleash for humankind: misinformation on a gigantic scale leading to misguided collective decision-making, job losses for millions of professionals, weaponised AI, enfeeblement resulting from over-dependence on AI, and mass disempowerment through the use of oppressive AI by a few. These AIleaders suggested that we treat it as we would a nuclear or pandemic threat, that we consider furthering it more collaboratively and setting up an international regulatory body to mitigate the high risks.

A few days ago, I spoke with a tech expert I had just met at a work event who announced quietly that he “despised” Yuval Noah Harari because “he got it wrong about history and he will get it wrong again about AI”. Despise is a strong word to come from a seemingly friendly man. I wondered why he felt such strong resentment towards Harari. A character from a movie I must have seen in the past emerged as a potential answer: a lonesome, frail teenage boy who is at best invisible to his peers and at worst bullied by them. At some point during his adolescence, he shut down his emotions, or perhaps had always struggled to connect with them. The experience was too painful, too unfamiliar, too hard to control, so he circumvented it, finding refuge in his unusually high IQ and his new computer. The computer became his best friend; his emotions and feelings, his worst enemies. While his peers were busy deepening their relationships with each other, exploring various vices, values, hopes and dreams in parks, bars and houses, this character built his relationships with DOS and Microsoft Adventure, with Cabal and Cadaver. He felt safe at home with his modern beige computer, whereas having people around him made him feel distinctly uncomfortable. He grew up to be fascinated with technology and later with AI.

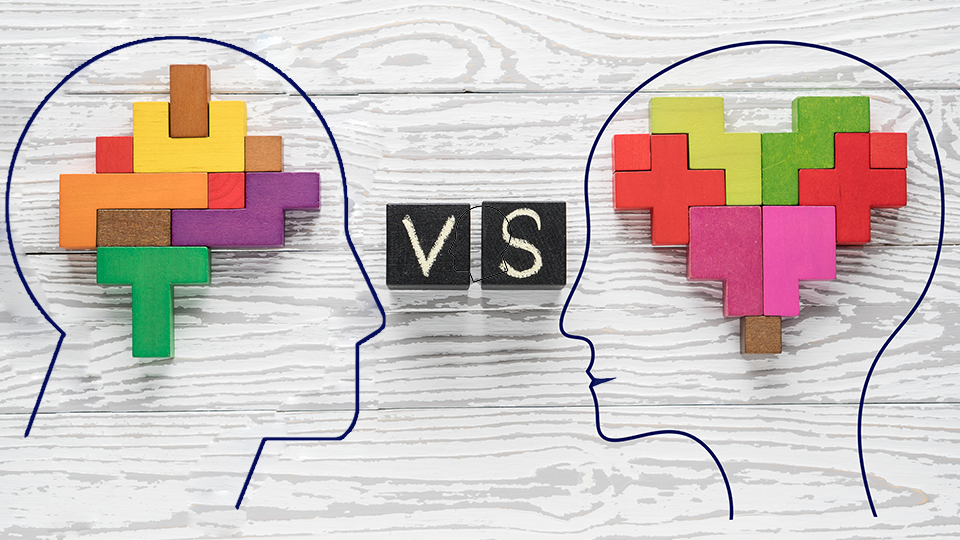

Is the disagreement and emerging polarisation around how to handle the approaching seismic changes and the supersonic speed of AI developments in effect a disagreement between human- centred and technology-centred worldviews? Might it be a debate between neuro- scientifically inaccurate but socially alive delineations between the left brain and right brain? Between free-flowing emotions and ultra logic? Between the fear of advanced technology and the fear of humans?

If we explore AI from the perspective of human interconnectedness and emotions, we may indeed be in a place where we are defending human nature. From this perspective, a world in which a robot is the daily companion of a lonely elderly person who has lost all human connection is unfathomable. “I would rather take my own life than have an AI companion!” declares my sister categorically and my son agrees when I float the idea of AI being used positively to combat loneliness. However, this idea would not seem so preposterous or disturbing to the character described above, who grew up with his computer as his best friend, finding solace in the mastery of

his perfectly logical arguments. The noughts and ones had always been his safety blanket against menacing human beings. By contrast, machines always seemed to welcome him with open displays. Perhaps it’s therefore unsurprising that the tech expert I spoke with the other day did not see the need to pause or regulate AI yet. “How can we regulate an unknown unknown? How can we regulate something that has not been developed yet?” A perfectly logical argument.

Meanwhile, as the increasingly polarised argument unfolds over how much human intervention should disrupt the future of generative AI, I (along with billions of others) stand wobbling on a trampoline of anxiety-inducing ignorance, preparing to dive into an ocean of new concepts and realities.

Before allowing myself to hop into any driverless taxi which only starts if you have your seatbelt on, I am determined to ensure that it truly cares for my safety. The learning curve ahead is steep: understanding the meaning, risks and benefits of tools, terms and applications such as ChatGPT, large language models, generative AI, artificial general intelligence and intelligent agents will take time and courage. This is step one.